Lateral Shift

& Glide

What is a lateral shift and how to apply a glide?

Working with patients who have a lateral shift and require the application of a glide can be difficult – especially if the applications and specifics aren’t quite clear. The truth is that theory and clinical realities are quite different. One of the biggest issues I see in clinical practice is the misunderstanding and incorrect application of lateral glides. The trunk deformity known as a lateral shift and the technique correcting this deformity known as a lateral glide are very often overlooked by clinicians during their clinical practice. Going over some definitions of trunk lateral shifts and glides, clinical examples - plus how the clinical practice and theory can work together with patients will help you work through this issue easily.

A lot of names, a lot of directions, a lot of confusion.

A few years ago, I published a few short videos on the internet which addressed mechanical corrections of various derangements. The purpose of those videos was to help my patients with the Home Exercise Program I recommended them. Most of the emails I have received included concerns regarding appropriate glide application. I’ve also noticed that a lot of clinicians were confused about how to name the direction of glides. When I was asked to write a few paragraphs about a clinical dilemma, lateral shift and glide immediately came to mind.

Let’s start with defining shifts and glides.

Shifts

A lateral shift is a position of the side glided spine. Lateral shift exists when the vertebra above is laterally flexed to right or left in relation to the vertebra below, carrying the trunk with it. As a result, the upper trunk and shoulders are shifted to right or left. If shoulder position is Right with respect to the hips we call this Right shift. If shoulder position is Left with respect to the hips we call this Left shift.

When we have Left shift with symptoms on Right - in other words we have shoulders moved away from the pain - we describe this as a contralateral shift. When shoulders are moved toward the painful side we describe this as an ipsilateral shift. An ipsilateral shift is not very common and appears in about 10% of all lateral shifts.

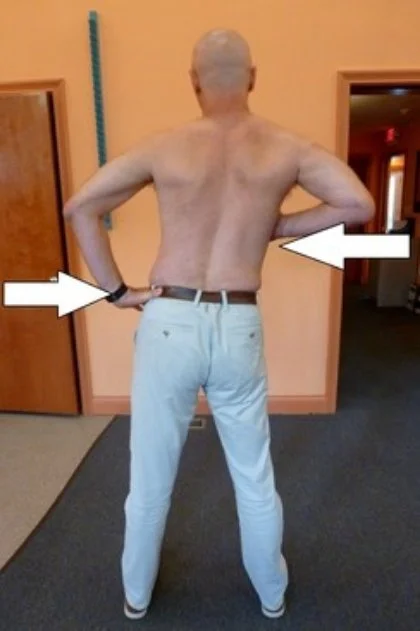

Corrected posture after application of clinician’s generated Left glide

Right lateral shift prior to correction

Glides

A glide is a trunk movement during the application of two opposite directed, parallel forces. One force is applied to the vertebra above, the other to the vertebra below.

The purpose of a glide is to correct a lateral shift. Glide direction is named after the direction of shoulder movement with respect to the hips. When shoulders move from right to left we call this movement Left glide. This brings a little bit of confusion in the clinical practice. I will explain it later.

Remember: Determination of a lateral shift by observation was found to be very unreliable, but determination of a positive side-glide test, based on alteration of the patient’s pain, was found to be highly reliable¹.

Left glide corrects R lateral shift

Self-generated glide in free standing

Patient places one hand on chest from the shifted shoulder side and the other hand on the iliac crest from the opposite side. One hand stabilizes hips, the other hand pushes chest in the pattern “two steps forward, one step back / 3 seconds in, 2 seconds off.” When the shift is overcorrected, meaning trunk was moved slightly over the midline, it is recommended to hold it for a few seconds.

Self-generated glide in a door frame

Patient standing in a door frame. Arms placed against door frame stabilize shoulders. Patient moves his hip toward shifted side in the pattern “two steps forward, one step back / 3 seconds in, 2 seconds off.” When the shift is overcorrected, meaning the trunk was moved slightly over the midline, it is recommended to hold it for a few seconds.

Self-generated glide against a wall

Patients stand with their shifted side next to the wall and the elbow is bent. Patient approaches the wall and places both shoulder and elbow against it. The leg nearest to the wall steps toward the outer leg. A hand placed on the iliac crest pushes hips toward the wall in the pattern “two steps forward, one step back / 3 seconds in, 2 seconds off.”When the hip reaches the wall the position can be maintained for a few seconds, then the nearest leg is moved toward the wall and the patient returns to the starting position.

Clinician-generated glide

Patient is in free standing with their feet apart, and arm from the shifted side bent in elbow to 90 degrees .As the clinician, you should stand on the patient’s shifted side in small lunge with forward leg in front of the patient. Your arms entwine patient’s hips, while your shoulder of the forwarded leg presses against patient’s bent arm, and head is attached to patient’s back. The force is coming from the therapist’s shoulder, which pushes the patient’s trunk, while arms stabilize hips. Movement is in the pattern “two steps forward, one step back / 3 seconds in, 2 seconds off.” When a lateral shift is overcorrected it can be maintained for a few seconds. Applied force has to be parallel to the floor. You have to avoid straightening his back during technique application. It would generate an upward force and produce a trunk flexion rather than a glide.

Common Clinical Concerns

-

In the case of the contralateral shift our goal is to close an intervertebral space and push a bulging disc inside to the original location. In the case of the ipsilateral shift our goal is to open an intervertebral space.

-

After reduction of a trunk deformity, you need to assess trunk restriction or obstruction. If necessary, add new direction of force. Force direction modification can be applied during gliding. We can also combine lateral gliding with an addition of extension. Extension should be generated right after reaching the point where the shift is overcorrected.

-

I believe a lateral shift can be also a result of a far posterior-lateral derangement, or far anterior-lateral derangement. Modification of force direction would be beneficial. The lateral shift can also be created by a unilateral muscle spasm or a unilateral soft tissue injury like burn or scar tissue.

-

Your patient’s response to the applied technique will guide you. Posterior, or latero- posterior force will aggravate symptoms or will be ineffective in the case of latero-anterior derangement and vice versa. For this reason, always follow the principles of minimal force. This means start with a technique generating a minimal force to achieve your goal and then assess your results. If there’s no response to the applied technique, proceed to a technique generating more force.

-

The first time a shift is corrected it very rarely remains. We have to teach our patient self-correction techniques and address it as a Home Exercise Program. I recommend initially 10 – 20 reps every hour. Poor sitting, walking, and bending are factors which initially cause recourse of deformity. All those issues have to be addressed during a physical therapy visit.

-

Although Robbin McKenzie invited gliding technique primary to correct a lateral derangement we can use it to correct a deformity related to a soft tissue dysfunction as well. With the correction of a soft tissue dysfunction I will expect better tolerance to gliding, no rapid changes, and a lack of centralization phenomenon.

-

As was mentioned above the direction of force can be strictly lateral, but it can also be modified based on the patient’s response and our clinical judgment.

-

For a clinician generated force I would follow the same principles as for high grade mobilization which are:

Any active systemic disease – Rheumatoid Arthritis, Ankylosing Spondylitis

Malignancy

Aneurysm

Past spinal surgery

Inflammatory conditions: Osteomyelitis, TB

Recent or Non union /consolidation

Severe osteoporosis

Practitioner lack of ability, skills, or training

Cord compression

Cauda Equina

Instability, or excessive hypermobility

Gross foraminal encroachment

Acute nerve root irritation or compression

Children / Teenager prior to puberty

Last trimester of pregnancy

Psychogenic disorder

Undiagnosed pain

Hemophilia

Long term corticosteroid medication

Lack of patient’s consent

When the Subjective and Physical examination do not agree

-

peripheralization of symptoms

increase of pain

reduction in ROM

no progress with trunk movement across midline in 2 – 3 visits

Theory vs. Reality

Unfortunately, a theory is simpler than in our practice. Here are multiple case examples from my clinical experience:

Case A: Patient with obvious shift states that he is straight and he was straight all his life. Analyzation of his posture in front of a mirror and on a picture made in the clinic did not convince him about his body deformity. A digital photo made in the clinic can be an easily accessible tool to record your findings and document them, if necessary.

Case B: Shift is so small that it can be noticed only by posture assessment without upper body clothing. How many clinicians assess the posture of undressed patients? If you don’t, please try it. You can find out a lot of clues to your case.

Case C: No evidence of a lateral shift but presented symptoms point toward a lateral derangement:

Unilateral asymmetrical pain,

no evidence of obstruction during forward flex,

no evidence of obstruction during trunk extension,

end range pain and obstruction only during a unilateral trunk side flexion and/or a unilateral side gliding.

Case D: Patient with long standing scoliosis developed lateral derangement and appeared in a clinic with a combination of long existing scoliosis increased by addition of a recently added lateral shift.

Those are only a few real life clinical dilemmas. Each of those dilemmas require a separate discussion, and approaches can be various based on clinical experience. I believe that a lot of clinicians who read my intake had some interesting and memorable cases as well as dilemmas about lateral shift and glide. Share your experiences and concerns to enrich our clinical wisdom by leaving a comment below.

¹ Donahue MS, Riddle DL, Sullivan MS. (1996). Intertester Reliability of a Modified Version of McKenzie’ Lateral Shift Assessments Obtained on Patients with Low Back Pain. Physical Therapy 76. 706-726

² McKenzie, R., & May, S. (2003). The Lumbar Spine: Mechanical Diagnosis & Therapy (2nd ed., Vol.1 & Vol.2). Raumati Beach, New Zealand: Spinal Publications New Zealand.